Some Poems

Biography

Images

Videos

Books

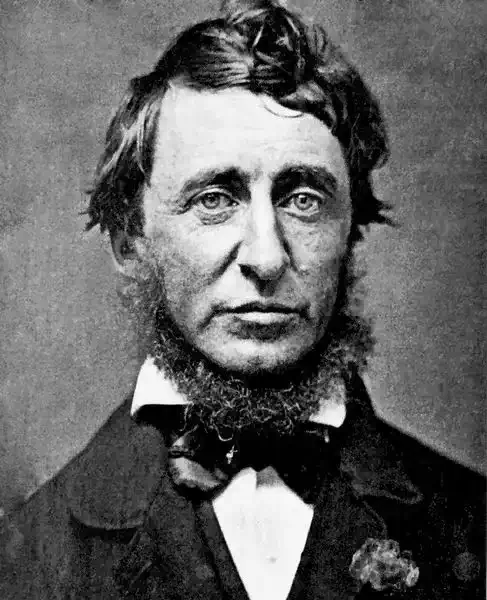

Henry David Thoreau (12 July 1817 – 6 May 1862)

Henry David Thoreau was an American author, poet, philosopher,

abolitionist, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, historian,

and leading transcendentalist He is best known for his book Walden, a

reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay Civil

Disobedience, an argument for individual resistance to civil government in

moral opposition to an unjust state.

Thoreau's books, articles, essays, journals, and poetry total over 20

volumes. Among his lasting contributions were his writings on natural history

and philosophy, where he anticipated the methods and findings of ecology

and environmental history, two sources of modern day environmentalism.

His literary style interweaves close natural observation, personal experience,

pointed rhetoric, symbolic meanings, and historical lore, while displaying a

poetic sensibility, philosophical austerity, and "Yankee" love of practical

detail. He was also deeply interested in the idea of survival in the face of

hostile elements, historical change, and natural decay; at the same time he

advocated abandoning waste and illusion in order to discover life's true

essential needs.

He was a lifelong abolitionist, delivering lectures that attacked the Fugitive

Slave Law while praising the writings of Wendell Phillips and defending

abolitionist John Brown. Thoreau's philosophy of civil disobedience later

influenced the political thoughts and actions of such notable figures as Leo Tolstoy,

Mohandas Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Thoreau is sometimes cited as an anarchist, though Civil Disobedience

seems to call for improving rather than abolishing government – "I ask for,

not at once no government, but at once a better government" – the direction

of this improvement points toward anarchism: "'That government is best

which governs not at all;' and when men are prepared for it, that will be the

kind of government which they will have." Richard Drinnon partly blames

Thoreau for the ambiguity, noting that Thoreau's "sly satire, his liking for

wide margins for his writing, and his fondness for paradox provided

ammunition for widely divergent interpretations of 'Civil Disobedience.'"

Early life and education

He was born David Henry Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts, into the

"modest New England family" of John Thoreau (a pencil maker) and Cynthia

Dunbar. His paternal grandfather was of French origin and was born in

Jersey.His maternal grandfather, Asa Dunbar, led Harvard's 1766 student

"Butter Rebellion", the first recorded student protest in the Colonies. David

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

Henry was named after a recently deceased paternal uncle, David Thoreau.

He did not become "Henry David" until after college, although he never

petitioned to make a legal name change. He had two older siblings, Helen

and John Jr., and a younger sister, Sophia. Thoreau's birthplace still exists

on Virginia Road in Concord and is currently the focus of preservation efforts.

The house is original, but it now stands about 100 yards away from its first

site.

Thoreau studied at Harvard University between 1833 and 1837. He lived in

Hollis Hall and took courses in rhetoric, classics, philosophy, mathematics,

and science. A legend proposes that Thoreau refused to pay the five-dollar

fee for a Harvard diploma. In fact, the master's degree he declined to

purchase had no academic merit: Harvard College offered it to graduates

"who proved their physical worth by being alive three years after graduating,

and their saving, earning, or inheriting quality or condition by having Five

Dollars to give the college." His comment was: "Let every sheep keep its own

skin", a reference to the tradition of diplomas being written on sheepskin

vellum.

Name pronunciation and appearance

Amos Bronson Alcott and Thoreau's aunt each wrote that "Thoreau" is

pronounced like the word "thorough". Although in current media (standard

American English) this word rhymes with "furrow",Edward Emerson wrote

that the name should be pronounced "Thó-row, the h sounded, and accent

on the first syllable."This would in fact rhyme with "thorough" as pronounced

in 19th century New England.

In appearance he was homely, with a nose that he called "my most

prominent feature." Of his face, Nathaniel

Hawthorne wrote: "[Thoreau] is as ugly as sin, long-nosed,

queer-mouthed, and with uncouth and rustic, though courteous manners,

corresponding very well with such an exterior. But his ugliness is of an

honest and agreeable fashion, and becomes him much better than

beauty."Thoreau also wore a neck-beard for many years, which he insisted

many women found attractive. However, Louisa May

Alcott mentioned to Ralph Waldo

Emerson that Thoreau's facial hair "will most assuredly deflect amorous

advances and preserve the man's virtue in perpetuity."

Return to Concord: 1837–1841

The traditional professions open to college graduates—law, the church,

business, medicine—failed to interest Thoreau, so in 1835 he took a leave of

absence from Harvard, during which he taught school in Canton,

Massachusetts. After he graduated in 1837, he joined the faculty of the

Concord public school, but resigned after a few weeks rather than administer

corporal punishment. He and his brother John then opened a grammar

school in Concord in 1838 called Concord Academy. They introduced several

progressive concepts, including nature walks and visits to local shops and

businesses. The school ended when John became fatally ill from tetanus in

1842 after cutting himself while shaving. He died in his brother Henry's

arms.

Upon graduation Thoreau returned home to Concord, where he met Ralph

Waldo Emerson through a mutual friend. Emerson took a paternal and at

times patronizing interest in Thoreau, advising the young man and

introducing him to a circle of local writers and thinkers, including Ellery

Channing, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne and his son

Julian Hawthorne, who was a boy at the time.

Emerson urged Thoreau to contribute essays and poems to a quarterly

periodical, The Dial, and Emerson lobbied editor Margaret Fuller to publish

those writings. Thoreau's first essay published there was Aulus Persius

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

Flaccus, an essay on the playwright of the same name, published in The Dial

in July 1840. It consisted of revised passages from his journal, which he had

begun keeping at Emerson's suggestion. The first journal entry on October

22, 1837, reads, "'What are you doing now?' he asked. 'Do you keep a

journal?' So I make my first entry to-day."

Thoreau was a philosopher of nature and its relation to the human condition.

In his early years he followed Transcendentalism, a loose and eclectic idealist

philosophy advocated by Emerson, Fuller, and Alcott. They held that an ideal

spiritual state transcends, or goes beyond, the physical and empirical, and

that one achieves that insight via personal intuition rather than religious

doctrine. In their view, Nature is the outward sign of inward spirit,

expressing the "radical correspondence of visible things and human

thoughts," as Emerson wrote in Nature (1836).

On April 18, 1841, Thoreau moved into the Emerson house. There, from

1841–1844, he served as the children's tutor, editorial assistant, and repair

man/gardener. For a few months in 1843, he moved to the home of William

Emerson on Staten Island,and tutored the family sons while seeking contacts

among literary men and journalists in the city who might help publish his

writings, including his future literary representative Horace Greeley.

Thoreau returned to Concord and worked in his family's pencil factory, which

he continued to do for most of his adult life. He rediscovered the process to

make a good pencil out of inferior graphite by using clay as the binder; this

invention improved upon graphite found in New Hampshire and bought in

1821 by relative Charles Dunbar. (The process of mixing graphite and clay,

known as the Conté process, was patented by Nicolas-Jacques Conté in

1795). His other source had been Tantiusques, an Indian operated mine in

Sturbridge, Massachusetts. Later, Thoreau converted the factory to produce

plumbago (graphite), which was used to ink typesetting machines.

Once back in Concord, Thoreau went through a restless period. In April 1844

he and his friend Edward Hoar accidentally set a fire that consumed 300

acres (1.2 km2) of Walden Woods. He spoke often of finding a farm to buy or

lease, which he felt would give him a means to support himself while also

providing enough solitude to write his first book.

Civil Disobedience and the Walden years: 1845–1849

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the

essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and

not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live

what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation,

unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the

marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that

was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner,

and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to

get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the

world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a

true account of it in my next excursion.”

— Henry David Thoreau, Walden, "Where I Lived, and What I Lived For

Thoreau needed to concentrate and get himself working more on his writing.

In March 1845, Ellery Channing told Thoreau, "Go out upon that, build

yourself a hut, & there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I

see no other alternative, no other hope for you." Two months later, Thoreau

embarked on a two-year experiment in simple living on July 4, 1845, when

he moved to a small, self-built house on land owned by Emerson in a

second-growth forest around the shores of Walden Pond. The house was in

"a pretty pasture and woodlot" of 14 acres (57,000 m2) that Emerson had

bought, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from his family home.

On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local tax collector, Sam

Staples, who asked him to pay six years of delinquent poll taxes. Thoreau

refused because of his opposition to the Mexican-American War and slavery,

and he spent a night in jail because of this refusal. (The next day Thoreau

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

was freed, against his wishes, when his aunt paid his taxes.) The experience

had a strong impact on Thoreau. In January and February 1848, he delivered

lectures on "The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to

Government" explaining his tax resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Bronson

Alcott attended the lecture, writing in his journal on January 26:

Heard Thoreau's lecture before the Lyceum on the relation of the individual

to the State– an admirable statement of the rights of the individual to

self-government, and an attentive audience. His allusions to the Mexican

War, to Mr. Hoar's expulsion from Carolina, his own imprisonment in Concord

Jail for refusal to pay his tax, Mr. Hoar's payment of mine when taken to

prison for a similar refusal, were all pertinent, well considered, and reasoned.

I took great pleasure in this deed of Thoreau's.

—Bronson Alcott, Journals (1938)

Thoreau revised the lecture into an essay entitled Resistance to Civil

Government (also known as Civil Disobedience). In May 1849 it was

published by Elizabeth Peabody in the Aesthetic Papers. Thoreau had taken

up a version of Percy Shelley's principle in the political poem The Mask of

Anarchy (1819), that Shelley begins with the powerful images of the unjust

forms of authority of his time – and then imagines the stirrings of a radically

new form of social action.

At Walden Pond, he completed a first draft of A Week on the Concord and

Merrimack Rivers, an elegy to his brother, John, that described their 1839

trip to the White Mountains. Thoreau did not find a publisher for this book

and instead printed 1,000 copies at his own expense, though fewer than 300

were sold. Thoreau self-published on the advice of Emerson, using Emerson's

own publisher, Munroe, who did little to publicize the book.

In August 1846, Thoreau briefly left Walden to make a trip to Mount

Katahdin in Maine, a journey later recorded in "Ktaadn," the first part of The

Maine Woods.

Thoreau left Walden Pond on September 6, 1847. At Emerson's request, he

immediately moved back into the Emerson house to help Lidian manage the

household while her husband was on an extended trip to Europe. Over

several years, he worked to pay off his debts and also continuously revised

his manuscript for what, in 1854, he would publish as Walden, or Life in the

Woods, recounting the two years, two months, and two days he had spent at

Walden Pond. The book compresses that time into a single calendar year,

using the passage of four seasons to symbolize human development. Part

memoir and part spiritual quest, Walden at first won few admirers, but later

critics have regarded it as a classic American work that explores natural

simplicity, harmony, and beauty as models for just social and cultural

conditions.

American poet Robert

Frost wrote of Thoreau, "In one book ... he surpasses everything we

have had in America."

John Updike wrote in 2004,

“A century and a half after its publication, Walden has become such a totem

of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience

mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit

saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible.”

Thoreau moved out of Emerson's house in July 1848 and stayed at a home

on Belknap Street nearby. In 1850, he and his family moved into a home at

255 Main Street; he stayed there until his death.

Later Years: 1851–1862

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and

travel/expedition narratives. He read avidly on botany and often wrote

observations on this topic into his journal. He admired William Bartram, and

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle. He kept detailed observations on

Concord's nature lore, recording everything from how the fruit ripened over

time to the fluctuating depths of Walden Pond and the days certain birds

migrated. The point of this task was to "anticipate" the seasons of nature, in

his words.

He became a land surveyor and continued to write increasingly detailed

natural history observations about the 26 square miles (67 km2) township in

his journal, a two-million word document he kept for 24 years. He also kept

a series of notebooks, and these observations became the source for

Thoreau's late natural history writings, such as Autumnal Tints, The

Succession of Trees, and Wild Apples, an essay lamenting the destruction of

indigenous and wild apple species.

Until the 1970s, literary criticsdismissed Thoreau's late pursuits as amateur

science and philosophy. With the rise of environmental history and

ecocriticism, several new readings if this matter began to emerge, showing

Thoreau to be both a philosopher and an analyst of ecological patterns in

fields and woodlots. For instance, his late essay, "The Succession of Forest

Trees," shows that he used experimentation and analysis to explain how

forests regenerate after fire or human destruction, through dispersal by

seed-bearing winds or animals.

He traveled to Quebec once, Cape Cod four times, and Maine three times;

these landscapes inspired his "excursion" books, A Yankee in Canada, Cape

Cod, and The Maine Woods, in which travel itineraries frame his thoughts

about geography, history and philosophy. Other travels took him southwest

to Philadelphia and New York City in 1854, and west across the Great Lakes

region in 1861, visiting Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul

and Mackinac Island. Although provincial in his physical travels, he was

extraordinarily well-read and vicariously a world traveler. He obsessively

devoured all the first-hand travel accounts available in his day, at a time

when the last unmapped regions of the earth were being explored. He read

Magellan and James Cook, the arctic explorers Franklin, Mackenzie and

Parry, David Livingstone and Richard Francis Burton on Africa, Lewis and

Clark; and hundreds of lesser-known works by explorers and literate

travelers. Astonishing amounts of global reading fed his endless curiosity

about the peoples, cultures, religions and natural history of the world, and

left its traces as commentaries in his voluminous journals. He processed

everything he read, in the local laboratory of his Concord experience. Among

his famous aphorisms is his advice to "live at home like a traveler."

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, many prominent voices in the

abolitionist movement distanced themselves from Brown, or damned him

with faint praise. Thoreau was disgusted by this, and he composed a

speech—A Plea for Captain John Brown—which was uncompromising in its

defense of Brown and his actions. Thoreau's speech proved persuasive: first

the abolitionist movement began to accept Brown as a martyr, and by the

time of the American Civil War entire armies of the North were literally

singing Brown's praises. As a contemporary biographer of John Brown put it:

"If, as Alfred Kazin suggests, without John Brown there would have been no

Civil War, we would add that without the Concord Transcendentalists, John

Brown would have had little cultural impact."

Death

Thoreau contracted tuberculosis in 1835 and suffered from it sporadically

afterwards. In 1859, following a late night excursion to count the rings of

tree stumps during a rain storm, he became ill with bronchitis. His health

declined over three years with brief periods of remission, until he eventually

became bedridden. Recognizing the terminal nature of his disease, Thoreau

spent his last years revising and editing his unpublished works, particularly

The Maine Woods and Excursions, and petitioning publishers to print revised

editions of A Week and Walden. He also wrote letters and journal entries

until he became too weak to continue. His friends were alarmed at his

diminished appearance and were fascinated by his tranquil acceptance of

death. When his aunt Louisa asked him in his last weeks if he had made his

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

peace with God, Thoreau responded: "I did not know we had ever

quarreled."

Aware he was dying, Thoreau's last words were "Now comes good sailing",

followed by two lone words, "moose" and "Indian". He died on May 6, 1862

at age 44. Bronson Alcott planned the service and read selections from

Thoreau's works, and Channing presented a hymn. Emerson wrote the

eulogy spoken at his funeral. Originally buried in the Dunbar family plot, he

and members of his immediate family were eventually moved to Sleepy

Hollow Cemetery (N42° 27' 53.7" W71° 20' 33") in Concord, Massachusetts.

Thoreau's friend Ellery Channing published his first biography, Thoreau the

Poet-Naturalist, in 1873, and Channing and another friend Harrison Blake

edited some poems, essays, and journal entries for posthumous publication

in the 1890s. Thoreau's journals, which he often mined for his published

works but which remained largely unpublished at his death, were first

published in 1906 and helped to build his modern reputation. A new,

expanded edition of the journals is underway, published by Princeton

University Press. Today, Thoreau is regarded as one of the foremost

American writers, both for the modern clarity of his prose style and the

prescience of his views on nature and politics. His memory is honored by the

international Thoreau Society.

Personal Beliefs

"Most of the luxuries and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only

not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind."

— Thoreau

Thoreau was an early advocate of recreational hiking and canoeing, of

conserving natural resources on private land, and of preserving wilderness as

public land. Thoreau was also one of the first American supporters of

Darwin's theory of evolution. He was not a strict vegetarian, though he said

he preferred that diet and advocated it as a means of self-improvement. He

wrote in Walden: "The practical objection to animal food in my case was its

uncleanness; and besides, when I had caught and cleaned and cooked and

eaten my fish, they seemed not to have fed me essentially. It was

insignificant and unnecessary, and cost more than it came to. A little bread

or a few potatoes would have done as well, with less trouble and filth."

Thoreau neither rejected civilization nor fully embraced wilderness. Instead

he sought a middle ground, the pastoral realm that integrates both nature

and culture. His philosophy required that he be a didactic arbitration between

the wilderness he based so much on and the spreading mass of North

American humanity. He decried the latter endlessly but felt the teachers

need to be close to those who needed to hear what he wanted to tell them.

He was in many ways a 'visible saint', a point of contact with the wilds, even

if the land he lived on had been given to him by Emerson and was far from

cut-off. The wildness he enjoyed was the nearby swamp or forest, and he

preferred "partially cultivated country." His idea of being "far in the recesses

of the wilderness" of Maine was to "travel the logger's path and the Indian

trail," but he also hiked on pristine untouched land. In the essay "Henry

David Thoreau, Philosopher" Roderick Nash writes: "Thoreau left Concord in

1846 for the first of three trips to northern Maine. His expectations were high

because he hoped to find genuine, primeval America. But contact with real

wilderness in Maine affected him far differently than had the idea of

wilderness in Concord. Instead of coming out of the woods with a deepened

appreciation of the wilds, Thoreau felt a greater respect for civilization and

realized the necessity of balance." On alcohol, Thoreau wrote: "I would fain

keep sober always... I believe that water is the only drink for a wise man;

wine is not so noble a liquor... Of all ebriosity, who does not prefer to be

intoxicated by the air he breathes?"

Social and political influence

"Thoreau's careful observations and devastating conclusions have rippled into

time, becoming stronger as the weaknesses Thoreau noted have become

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

more pronounced ... Events that seem to be completely unrelated to his stay

at Walden Pond have been influenced by it, including the national park

system, the British labor movement, the creation of India, the civil rights

movement, the hippie revolution, the environmental movement, and the

wilderness movement. Today, Thoreau's words are quoted with feeling by

liberals, socialists, anarchists, libertarians, and conservatives alike."

— Ken Kifer

Thoreau's political writings had little impact during his lifetime, as "his

contemporaries did not see him as a theorist or as a radical, viewing him

instead as a naturalist. They either dismissed or ignored his political essays,

including Civil Disobedience. The only two complete books (as opposed to

essays) published in his lifetime, Walden and A Week on the Concord and

Merrimack Rivers (1849), both dealt with nature, in which he loved to

wander."Nevertheless, Thoreau's writings went on to influence many public

figures. Political leaders and reformers like Mahatma Gandhi, President John

F. Kennedy, civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr., Supreme Court

Justice William O. Douglas, and Russian author Leo Tolstoy all spoke of being

strongly affected by Thoreau's work, particularly Civil Disobedience, as did

"right-wing theorist Frank Chodorov devoted an entire issue of his monthly,

Analysis, to an appreciation of Thoreau."Thoreau also influenced many artists

and authors including Edward Abbey, Willa Cather, Marcel Proust, William

Butler Yeats, Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, E. B. White,

Lewis Mumford, Frank Lloyd Wright, Alexander Posey and Gustav

Stickley.Thoreau also influenced naturalists like John Burroughs, John Muir,

E. O. Wilson, Edwin Way Teale, Joseph Wood Krutch, B. F. Skinner, David

Brower and Loren Eiseley, whom Publishers Weekly called "the modern

Thoreau." English writer Henry Stephens Salt wrote a biography of Thoreau

in 1890, which popularized Thoreau's ideas in Britain: George Bernard Shaw,

Edward Carpenter and Robert Blatchford were among those who became

Thoreau enthusiasts as a result of Salt's advocacy.

Mahatma Gandhi first read Walden in 1906 while working as a civil rights

activist in Johannesburg, South Africa. He first read Civil Disobedience "while

he sat in a South African prison for the crime of nonviolently protesting

discrimination against the Indian population in the Transvaal. The essay

galvanized Gandhi, who wrote and published a synopsis of Thoreau's

argument, calling its 'incisive logic . . . unanswerable' and referring to

Thoreau as 'one of the greatest and most moral men America has

produced.'" He told American reporter Webb Miller, "[Thoreau's] ideas

influenced me greatly. I adopted some of them and recommended the study

of Thoreau to all of my friends who were helping me in the cause of Indian

Independence. Why I actually took the name of my movement from

Thoreau's essay 'On the Duty of Civil Disobedience,' written about 80 years

ago."

Martin Luther King, Jr. noted in his autobiography that his first encounter

with the idea of non-violent resistance was reading "On Civil Disobedience" in

1944 while attending Morehouse College. He wrote in his autobiography that

it was

Here, in this courageous New Englander's refusal to pay his taxes and his

choice of jail rather than support a war that would spread slavery's territory

into Mexico, I made my first contact with the theory of nonviolent resistance.

Fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system, I was so

deeply moved that I reread the work several times.

I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral

obligation as is cooperation with good. No other person has been more

eloquent and passionate in getting this idea across than Henry David

Thoreau. As a result of his writings and personal witness, we are the heirs of

a legacy of creative protest. The teachings of Thoreau came alive in our civil

rights movement; indeed, they are more alive than ever before. Whether

expressed in a sit-in at lunch counters, a freedom ride into Mississippi, a

peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia, a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama,

these are outgrowths of Thoreau's insistence that evil must be resisted and

that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice.

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

American psychologist B. F. Skinner wrote that he carried a copy of

Thoreau's Walden with him in his youth. and, in 1945, wrote Walden Two, a

fictional utopia about 1,000 members of a community living together inspired

by the life of Thoreau. Thoreau and his fellow Transcendentalists from

Concord were a major inspiration of the composer Charles Ives. The 4th

movement of the Concord Sonata for piano (with a part for flute, Thoreau's

instrument) is a character picture and he also set Thoreau's words.

Anarchism

Thoreau's ideas have impacted and resonated with various strains in the

anarchist movement, with Emma Goldman referring to him as "the greatest

American anarchist." Green anarchism and Anarcho-primitivism in particular

have both derived inspiration and ecological points-of-view from the writings

of Thoreau. John Zerzan included Thoreau's text "Excursions" (1863) in his

edited compilation of works in the anarcho-primitivist tradition titled Against

civilization: Readings and reflections. Additionally, Murray Rothbard, the

founder of anarcho-capitalism, has opined that Thoreau was one of the

"great intellectual heroes" of his movement. Thoreau was also an important

influence on late 19th century anarchist naturism. While globally, Thoreau's

concepts also held importance within individualist anarchist circles in Spain,

France, and Portugal.

Contemporary Critics

Although his writings would later receive widespread acclaim, Thoreau's

ideas were not universally applauded by some of his contemporaries in

literary circles. Scottish author Robert Louis

Stevenson judged Thoreau's endorsement of living alone and apart

from modern society in natural simplicity to be a mark of "unmanly"

effeminacy and "womanish solitude", while deeming him a self-indulgent

"skulker." Nathaniel Hawthorne was also critical of Thoreau, writing that he

"repudiated all regular modes of getting a living, and seems inclined to lead a

sort of Indian life among civilized men." In a similar vein, poet John

Greenleaf Whittier detested what he deemed to be the "wicked" and

"heathenish" message of Walden, decreeing that Thoreau wanted man to

"lower himself to the level of a woodchuck and walk on four legs."

In response to such criticisms, English novelist George

Eliot, writing for the Westminster Review, characterized such critics as

uninspired and narrow-minded:

People—very wise in their own eyes—who would have every man's life

ordered according to a particular pattern, and who are intolerant of every

existence the utility of which is not palpable to them, may pooh-pooh Mr.

Thoreau and this episode in his history, as unpractical and dreamy.

Works:

Aulus Persius Flaccus (1840)

The Service (1840)

A Walk to Wachusett (1842)

Paradise (to be) Regained (1843)

The Landlord (1843)

Sir Walter Raleigh (1844)

Herald of Freedom (1844)

Wendell Phillips Before the Concord Lyceum (1845)

Reform and the Reformers (1846–48)

Thomas Carlyle and His Works (1847)

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849)

Resistance to Civil Government, or Civil Disobedience (1849)

An Excursion to Canada (1853)

Slavery in Massachusetts (1854)

Walden (1854)

A Plea for Captain John Brown (1859)

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

Remarks After the Hanging of John Brown (1859)

The Last Days of John Brown (1860)

Walking (1861)

Autumnal Tints (1862)

Wild Apples: The History of the Apple Tree (1862)

Excursions (1863)

Life Without Principle (1863)

Night and Moonlight (1863)

The Highland Light (1864)

The Maine Woods (1864)

Cape Cod (1865)

Letters to Various Persons (1865)

A Yankee in Canada, with Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers (1866)

Early Spring in Massachusetts (1881)

Summer (1884)

Winter (1888)

Autumn (1892)

Miscellanies (1894)

Familiar Letters of Henry David Thoreau (1894)

Poems of Nature (1895)

Some Unpublished Letters of Henry D. and Sophia E. Thoreau (1898)

The First and Last Journeys of Thoreau (1905)

Journal of Henry David Thoreau (1906)

The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau edited by Walter Harding and

Carl Bode (Washington Square: New York University Press, 1958

www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive

POLITICAL THEORY - Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau documentary

Why Every Student in America Should Read Henry David Thoreau's "Walden"

Henry David Thoreau: A Life

Discover the Real Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau and Civil Disobedience

Be a Loser - The Philosophy of Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau's Civil Disobedience

Civil Disobedience Audiobook by Henry David Thoreau

Interesting facts about Henry David Thoreau

Walden by Henry David Thoreau | In Depth Summary & Analysis

Thoreau at 200: Reflections on "Walden"

A journey through Henry David Thoreau's Maine woods

Episode #083 Henry David Thoreau

Walden (FULL Audiobook)

Henry David Thoreau and the Necessity of Conviction

Henry David Thoreau vu par Michel Onfray

WALDEN by Henry David Thoreau - FULL AudioBook - Part 1 (of 2) | Greatest AudioBooks

Reflect On Henry David Thoreau’s Vision Of Walden Pond | The Daily 360 | The New York Times

Henry David Thoreau: Why Being a 'Loser' Is a Win

The American Diogenes—Henry David Thoreau's Living Philosophy

Thoreau's simple life at Walden

Henry David Thoreau - Walking

Unlocking the Power of Solitude: The Wisdom of Henry David Thoreau

The Dark Side of Hustle Culture | Henry David Thoreau Walden

Walden by Henry David Thoreau | Brief Plot Summary

Walden Film

LIFE WITHOUT PRINCIPLE by Henry David Thoreau - FULL AudioBook 🎧📖 | Greatest🌟AudioBooks

Walden by Henry David Thoreau Book Review

Simplify, Simplify | A Philosophy of Needing Less

Walden by Henry David Thoreau | Chapter 18

Dickinson — Thoreau’s Cabin | Apple TV+

Henry D. Thoreau: A Pioneer of Transcendentalism

Civil disobedience | सविनय अवज्ञा | henry david thoreau | गांधीजी की 11 सूत्री मांग

Henry David Thoreau - La désobéissance civile

Civil Disobedience by Henry David Thoreau Explained

Passage: Henry David Thoreau's 200th birthday

Walden, de Henry David Thoreau | RESEÑA

Walden by Henry David Thoreau | Chapter 1

Sobre o ensaio “A desobediência civil”, de Henry David Thoreau (Obra do PAS/UnB)

S04E34: Caminhada, de Henry David Thoreau

The Maine Woods by Henry David THOREAU read by Expatriate Part 1/2 | Full Audio Book

Walden by Henry David Thoreau | Chapter 7

Walden by Henry David Thoreau | Chapter 16

Walden by Henry David Thoreau | Chapter 17

The Life Of Henry David Thoreau

How to Pronounce Henry David Thoreau? (CORRECTLY)

30 Best Henry David Thoreau Quotes that will Inspire you. | Timeless Quotes

Henry David Thoreau Quotes That Will Make You Realize What You Should Do In Your Life!

Walden by Henry David Thoreau | Chapter 13

Escritas.org

Escritas.org